David Brin offers a different take on the first contact novel. Read my review at the Free Press.

Tag Archives: books

Book Review: Technicolor Ultra Mall

I don’t want to call Ryan Oakley’s 2012 Aurora nominee A Clockwork Orange 2.0. There are so many other ways to describe it: it’s raw and bloody; beautiful and horrific; staccato like a machine-gun; and as fresh as it is familiar. His homage to Burgess’ 1962 classic could hardly be more faithful, yet it stands alone, quintessentially a product of now, though with a degree of the timelessness which cemented that earlier novel as a classic.

LJ Ahoy

My first Library Journal review has now been published, though it was written some time ago. It’s indexed online but viewable only in the print edition or the subscriber database. In case you were wondering, I reviewed the math text, X and the City, from Princeton’s academic press. The verdict? You’ll have to track down my review to find out.

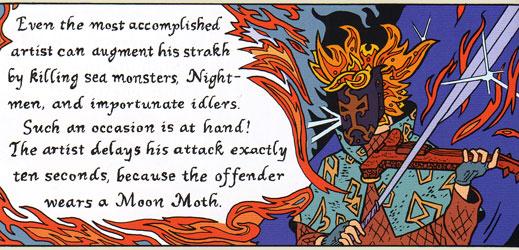

Book Review: The Moon Moth

Of course, [Jack] Vance’s brand of science fiction is atypical, to say the least. This story is among those possessing the least overtly fantastical elements of any of his work, and yet it still feels awfully fantastical. The alien culture he describes is stylish, exotic, perhaps vaguely politically anachronistic. In other words, it stands up against McCaffrey, Le Guin, or Lieber at their world-building best, possessing the same sort of fantasy sensibility one finds in his own cross-genre Dying Earth stories, though The Moon Moth is strictly free of supernatural elements.

Read my full review at Revolution Science Fiction.

Book Review: 1Q84

Before its English-language release, even, in fact, before the original Japanese books were published, speculation ran rampant about this long novel. What would it be about? What did it have to do with George Orwell’s original work? What was the significance of the “Q”, replacing the nine of the original title?

Haruki Murakami is unquestionably the most well-known Japanese-language writer in the international literary scene. He’s also critically-acclaimed, having collected a litany of high-profile literary awards throughout the world. He’s made odds-makers short lists for the Nobel Prize in Literature the last several years, though he hasn’t won, yet.

1Q84 is a 900-page opus. Originally published in three volumes in Japan, the individual books really don’t stand alone. As with Tolkien’s “trilogy”, it was likely a question of length alone. The English translation has been published as a single volume in both Canada and the United States, by publishers Bond Street Books and Knopf, respectively.

The letter Q and the number 9 in Japanese are homonyms. Said out loud, the title of Murakami’s latest is identical to Orwell’s 1984, when the numbers are pronounced in Japanese. The attractive hardcover also has some unusual typesetting. The book title and page numbers are mirror-reversed on opposite pages. The Q suggests we are in a different world than that imagined by Orwell. The typesetting suggests we are in a different world from our own.

Set in 1984 Tokyo, the novel follows the stories of two apparently unconnected protagonists in alternating chapters. At the novel’s opening, Aomame is a young woman on her way to an important business meeting but is stuck in traffic on the expressway. Dressed smartly and professionally, she nevertheless takes the unorthodox action of leaving her taxi and climbing over the guard rail, climbing down a rickety emergency stairway in order to make her meeting on time. We soon discover why the timing was so important: she’s a professional hit-woman on her way to kill a man.

Tengo, by contrast, is a gentle young man meeting with his editor about an unusual manuscript submission for a literary contest. A part-time math instructor and technically-competent amateur writer, he pushes his editor to consider the unpolished, but compelling story as a finalist. There’s something . . . magical about it. But it will never win, as rough as it is. So his editor, completely disdainful of either convention or ethics, suggests Tengo secretly rewrite the whole thing for the original author, as part of a conspiracy between the three of them.

Tengo doesn’t realize what he is getting himself into with his decision to rewrite the novella, Air Chrysalis. He obtains the permission of its mysterious author, the 17-year-old Fuka-eri, but still feels uneasy. As he learns more about the girl and her history, he begins to suspect that the events of the story may not be entirely fiction.

A ten-year-old girl living in a frightening cult, locked up in an ice-cold shed for 10 days with a dead, blind goat as punishment for some religious transgression — the mysterious Little People who are neither good nor evil, but clearly dangerous — the air chrysalis, whose purpose is unclear: there are hints that these are more than the figments of a teenage girl’s imagination.

But it’s Aomame, who can hardly be said to have an ordinary life to begin with, who is the first to notice that things in the world seem slightly off. She starts noticing odd items in the news, references to both local and global events of the past few years that she can’t believe she wouldn’t have heard of before. A huge shoot-out between Japanese police and an armed radical group with far-reaching policy consequences. A major US-Soviet joint project in space, at the height of the Cold War.

Of course Murakami is known for taking us down the rabbit hole. In the magical realism tradition of Borges, and Kafka before him, the Japanese author’s approach is to simply introduce one inexplicable event after another into his characters’ lives. In fact, down the rabbit hole may not be the right analogy for 1Q84 at all. One can climb back out of a rabbit hole. It’s more like the world itself has been twisted askew — as if somebody turned a crank and reality was irreparably bent into a new shape.

It’s how his characters cope with these situations Murakami throws at them which makes the story. Aomame spends hours going through microfilmed periodicals at the library, sure that the world she lives in has subtly changed from what it was before. But all the newspapers, the history books, even the collective memories of humankind are all consistent with each other, so how can she be sure it wasn’t her own mind which suffered the catastrophic change? Orwell understood the importance of a collective understanding of truth: propaganda and false histories featured heavily in his novel. Unmoored from history, we are helplessly adrift.

Murakami has a tendency to spend pages describing the mundane day-to-day tasks of his characters. But it’s not long-windedness that causes him to describe in detail a trip to the grocery store, or the preparation of miso soup and grilled fish. The mundane in his fiction serves as a counter-point, placing in stark contrast the disequilibrium his characters must contend with as logic is suspended around them.

As in real-life, the emotional and intellectual challenges his characters face are not resolved over hours or days, but months. Close to a year goes by in the course of this novel, and indeed, this timescale is typical of Murakami. Meanwhile, life goes on. Chores must be performed, classes must be taught.

Murakami’s Japanese perspective combined with his deep knowledge and love of Western literature produce a voice that is utterly unique. Though magical realism in the tradition of Borges is a defining part of Murakami’s literary DNA, his plotting takes less from the Argentine writer than Raymond Chandler, master of the hard-boiled detective novel.

Unasked for, Murakami’s characters find themselves embroiled in mysteries as convoluted as Philip Marlowe’s. Their response, a resigned stoicism, is deeply Japanese. But read the author’s translation work for more hints. The Great Gatsby, The Catcher in the Rye — caught up in forces beyond their control, you can see Holden Caulfield’s aimless acceptance, Jay Gatsby’s guarded hope. “Fatalism tempered with optimism” is the best one-phrase description I’ve managed to come up with for Murakami’s work.

Is 1Q84 the career-defining masterpiece some were predicting it would be? I don’t feel qualified to say. I think it’s on a par with The Wind-up Bird Chronicle and Kafka by the Shore, which I consider his strongest works to date. It’s connection to the original 1984 is . . . indirect.

Orwell’s great fear was a trend towards totalitarian government. Murakami focuses, albeit obliquely, on religious cults, a topic he has tackled in his non-fiction (Underground: The Tokyo Gas Attack). Both types of institution enslave minds. But his intention is probably less a direct indictment of the cult mentality than a reiteration of the larger themes we’ve seen in his previous fiction: societal alienation; existential angst.

If Murakami is warning us about anything, it’s probably the dangers of becoming disconnected from our lives. Both political and religious extremism are, in that view, just symptoms of the problem.

(Bond Street Books, 2011)

Reprinted with permission from The Green Man Review

Copyright (2012) The Green Man Review

Book Review: Vortex

When I read Spin back in 2005, I was awoken to a whole new world of what science fiction could do. This guy, Robert Charles Wilson, a veteran by any standard yet new to me, balanced the grandly cosmic and the tragically human with a subtlety that’s almost sublime. But when I read his follow-up to the story of the Spin and the Hypothetical beings behind it, I felt like he lost that balance.

While Spin proposed one of the great SF scenarios, the sort of “Big Idea” that would make any Golden Age or contemporary hard science fiction writer proud, Wilson quickly made it clear that it was those insignificant, ant-like humans whose story he was really interested in telling. In Axis, it seems, he was suddenly more interested in exploring that Big Idea. But the characters didn’t grab me and without them as an anchor, I didn’t feel the need to find out the truth about the Hypotheticals.

But he pulled me back in with Vortex. Suddenly I cared about the characters again, the returning cast as well as the new ones. Coincident with, if not because of that, he got me interested in the central mystery of the Hypotheticals themselves. These are the inscrutable beings who set up the Spin, a local distortion in time with the effect of taking humanity to the death throes of its own Sun within a single generation. By the end of Vortex, we get to find out why, and the answer is, to me, appropriate and satisfying.

The story follows a dual narrative in alternating chapters. In the immediate aftermath of the Spin, vagrancy and mental illness are still way up, while a world tries to cope with being thrown epochs into the future, surviving the overwhelming energy of their own expanded Sun only at the mercy of an inscrutable and possibly indifferent alien technology.

Sandra is one of these overworked mental health professionals, Officer Bose is one good cop in a deeply crooked system, and Orrin Mather is the recently remanded ward of the state neither of them can quite figure out.

It’s in Orrin Mather’s notebooks that we find the second narrative, but, paradoxically, it tells the story of two people who will live nearly 10, 000 years in the future. Turk Findley we last saw at the close of the previous book: taken up bodily into a Hypothetical technology called a temporal arch. His new friend, Treya, was born in the era he finds himself expelled into. Together they are under the custody of an emotionally- and mentally-linked political collective called Vox, which hopes to meet and, perhaps, become one with the Hypotheticals. For the two of them, alone amongst the enforced consensus of Vox, there is doubt as to whether this is a desirable outcome.

Whether Mather, a mentally-challenged, barely literate young man, could have written the stories found in these notebooks himself is dubious. But the possibility that they are true is far less likely (if not to the reader).

I wasn’t sure if I would read the final book in this trilogy after being let down by the second. But I’m glad I did. If you’ve already read Axis and were thinking of skipping Vortex, you should reconsider.

If you’ve read Spin only, that’s a tougher call. Wilson himself has said that Spin is a stand-alone novel that happens to have two sequels. You can’t really skip the middle novel and jump to the end, as the latter two are more of a package deal. So the question is, is it worth reading Axis, which is good, but not great, in order to set up Vortex?

The story of the characters from Spin is over by novel’s end, but the mystery of the Hypotheticals remains. If you want resolution to the Big Idea plot points, keep reading. If you were more interested in the human side of things, you can reasonably stop with Spin. Wilson’s Hugo-winner is an exceptional novel taken on its own. But the series as a whole has its merits, as well.

(Tor, 2011)

Reprinted with permission from The Green Man Review

Copyright (2012) The Green Man Review

Tuesday Links (05/22/12)

The Revolution SF Watercooler: HP Lovecraft and Racism: “The real issue is whether a reader finds his work worthy despite the worst parts of his personality.”

The Avengers Inside Hopper’s Iconic Nighthawks Painting: Yep.

Going to a rock concert is different when you’re 60: This guy writing for the Globe and Mail? I know this guy. Awesome guy.

Book Review: Earthbound

As series go, the trilogy comprised of Joe Haldeman’s Marsbound, Starbound, and Earthbound novels is a bit of an oddity. On the one hand, each book has been a direct sequel of the previous, picking up the narrative right where it was left off. Carmen Dula also remains the protagonist and narrator throughout the books. On the other hand, the plots of each novel, while hardly self-contained, could hardly be more different.

Read the rest of my review at Revolution Science Fiction.

Book Review: A Bridge of Years

It’s hard to write a time-travel story without it turning into a metaphor for something. The past and the future are too pregnant with meaning; too tied into what we are. The immutability of the past doesn’t prevent us from obsessing over it. The uncertainty of the future doesn’t discourage us from trying to fix it securely. We, perhaps alone amongst the animals, live and breathe time.

Tuesday Links (05/01/12)

How Shakespeare Changed Everything: My grade 12 English teacher was right. You don’t have to like Shakespeare, but being culturally literate means being familiar with his major works.

Songs from District 12: Did the Hunger Games produce a movie soundtrack worth buying?

Class dismissed: “Half of new bachelor’s degree grads are either unemployed or underemployed, according to the Associated Press. . . . In my darker moments, I sometimes wonder if the root of the problem with public higher education in America is that it was designed to create and support a massive middle class. . . . When the goal of a prosperous middle class was tacitly dismissed, dominos started to fall. “